Five Months of Winter(2021)

Five Months of Winter is a multi-disciplinary, autobiographic project. It is composed of a series of portraits, polaroid pictures, collages, and a book. It aims to portray a mental and emotional state in a foreign country during the second year of the pandemic and a hard winter. The book works as a kind of journal that collects thoughts and analyses throughout the construction of the project.

(i) The Trees Can’t Stand The Weight

The Trees Can’t Stand The Weight is a fight: against time, gravity and adversity. Time in two layers. Firstly, the natural time associated with its passing through the seasons, and secondly, the time after death, the decomposition of organic bodies, and the possibility to fight it through the photographic capture which generates a new temporality in which the trees will remain forever dead — without disappearing. Gravity is a natural law that keeps us tied to the ground; the only purpose of a tree is to grow and fight it. These pictures work as a testimony of that struggle. The use of winter, trees, and their death is an effort to confront us, humans, with our own weakness and mortality: a reminder of how it can also be a valid choice to trust in gravity and let ourselves break and fall. Having been fighting something throughout our whole life does not mean that we cannot rest on the ground. Additionally, it confronts the notion of landscape photography and portraits. On the one hand, it corresponds with the Vanitas still life pictures in its theme of mortality and its capture. On the other hand, just like in portrait tradition, we have a vertical composition and, more importantly, a clear protagonist, the trees. It is trees, the model, that ask for certain formal decisions to be taken at the moment of the capture. Somehow, not being able to move the model and make it adapt to one’s needs or vision, forces us to mold our work towards the needs of the model. This practice of portraying a model that cannot be asked to pose forces the artist to respond to it — instead of the other way around. As a result, the final image is a perfect communion in which the artist is portrayed through his own portrayal of the model.

— Black and White Photography

(ii) Muffled Bliss

Muffled Bliss works as the representation of an intimate soundscape. The instant quality of polaroid pictures evokes a visceral and urgent feeling of preserving a moment. Landscape photography, in turn, does not show much due to its quality but rather sets the viewer into a mood and a context. The size and the physical connection to the pictures produce an immersive effect. Capturing the silence and stillness of the vast empty landscape in front of us.

— Polaroid Pictures

(iii) Osterberg Blizzard

Osterberg Blizzard makes use of material in a chaotic way messes with the memories represented by the polaroid pictures gathered during previous months of winter. The system of construction is based on what would be the visualization of a blizzard: unclear images, a lot of speed and movement, a blur covering everything so that you cannot seem to focus on one thing because you have this curtain of chaos falling in front of you. It incorporates the blizzard experience inside and outside, the construction system corresponding to the outside, and the selection of the used material to the inside. This selection derives from the feeling of being trapped and having to use what you have at hand: a limited amount of pictures and a scanner.

The final composition is a result of the pictures that had fallen onto the surface of the scanner like snow piling up, being moved around by the wind — in this case, a body that is running out of time just like the last month of winter clinging to not letting go. A viewerless performance.

— Collage

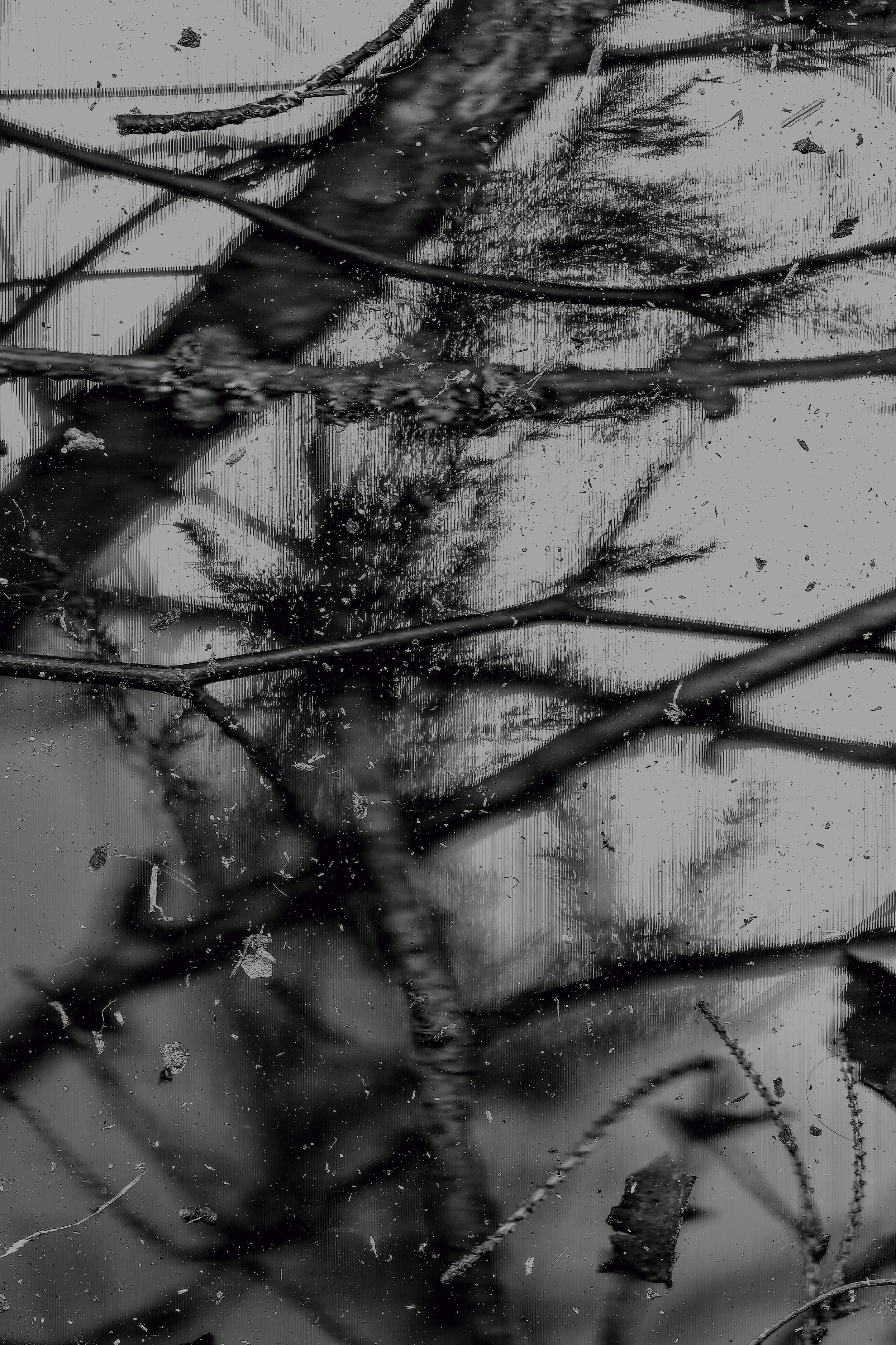

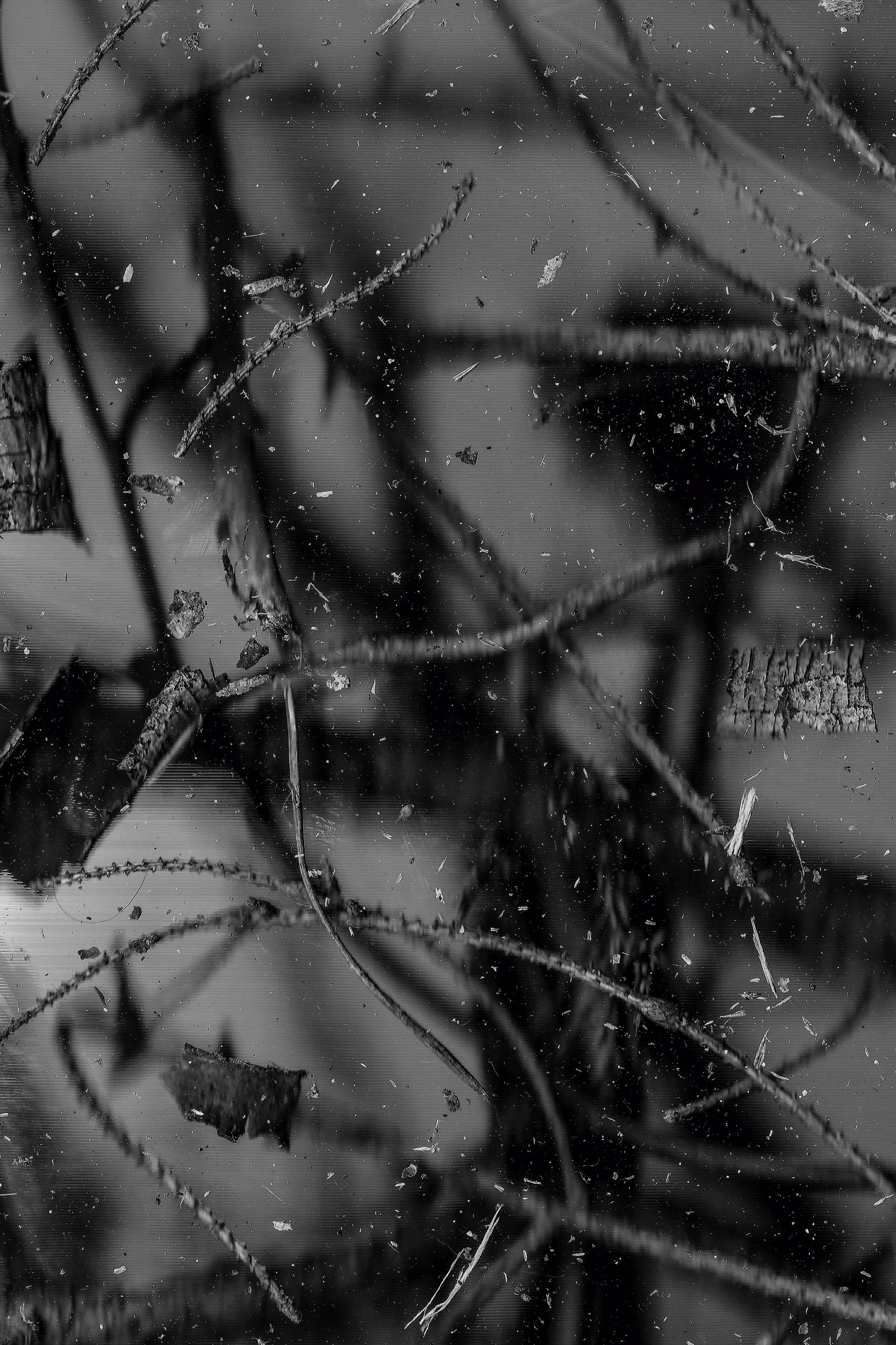

(iv)It Was Not the Forest Who Gave Me Nightmares

It was not the forest who gave me nightmares, transits among the relationship between mankind and the forest. This one was a refuge, as well as a source of hidden dangers. The images are formed through the scanning of still life scenes composed of branches and leaves from a nearby forest, a collection of things we bring back, a collection that includes our sensations, fears, and imagination, and it is with this operation that a separation between the original and the resulting image is created. The index of the material world translated into our nightmares. This acts also a transfer of information from a three-dimensional space to a two-dimensional one, from the wilderness to a confined collage. It shows us how reality and fantasy can get blended but also detached from each other just as dreams and nightmares do from reality.

— Collage